Gallo-Greek Votives

Table of Contents

Votives

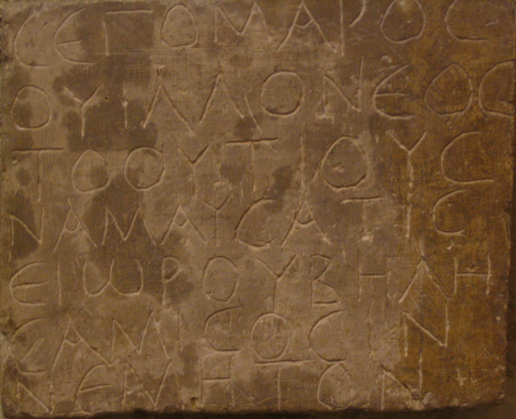

Segomaros’ votive to Bēlēsama

σεγομαρος ουιλλονεος τοουτιους ναμαυσατις ειωρου βηλησαμι σοσιν νεμητον

segomaros uilloneos toutius namausatis eiuru bēlēsami sosin nemēton

Translation:*

Segomaros (“Powerful”), chief magistrate of Namausos (Nîmes), dedicated unto Bēlēsama this nemeton.

*There’s always some uncertainty reading Gaulish. Segomāros’ titles have also been read as, “son of (the chief?), citizen of Nîmes,” for example.

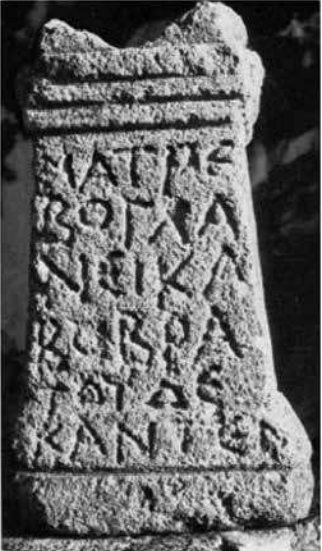

Votive to the Glanican Matres

ματρεβο γλανεικαβο βρατου δεκαντεν

matrebo glanicabo bratu decanten

“To the Glanican Mothers, due tithe.”

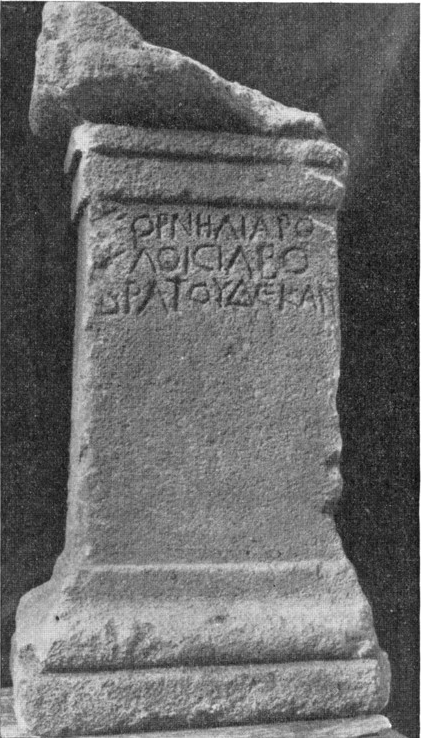

Cornelia’s votive to the Rocloisias

↑ Return to Contentsκορνελια ρο κλοισιαβο βρατου δεκαντ[εν]

cornelia ro cloisiabo bratu decanten

“Cornelia [gave] unto the Ro Cloisias the due tithe.”

[E]porix’s votive to Belenos

[ ]πορειζ ιουγιλλιακος δεδε ↑ βρατου ↑ βελεινο

[ ]porix iugilliacos dede ↑ bratu ↑ beleno

“[E]porix of Iugillos gave the due [tithe?] unto Belenus”

This dedicant’s name is damaged, and it has been variously proposed as Eporix ‘Horse King,’ Veporix, ‘Speech King,’ or Ateporix ‘Protector King?’ A similar name to Ateporix—Voteporix—is attested both in Ogam and Brittonic, but would be too long to fit the basin’s inscription. Some scholars are of the opinion that the name Ateporix would have left some trace that is not visible, making Eporix or Veporix more likely.

![[E]porix’s votive to Belenos A line drawing of the inscription. Unlike most votives, this one is on the rim of a basin, which makes it a single line of text all the way across, until the end where the word "bratu" is inscribed directly above the God Belenos' name. Source: https://www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_1968_num_12_1_1418](https://skribbatous.org/user/pages/02.sanestos/rata/gallo-greek/beleino1.png)

![[E]porix’s votive to Belenos Black and white photo of the limestone basin inscribed with the votive, shown from the side. The inscription is rustic Greek capitals, the basin is very worn and pock marked and cracked. It is shaped like a bowl, but not quite as tall as a cereal bowl would be (proportionally speaking). It is 61 centimeters in diameter.](https://skribbatous.org/user/pages/02.sanestos/rata/gallo-greek/beleino2.png)

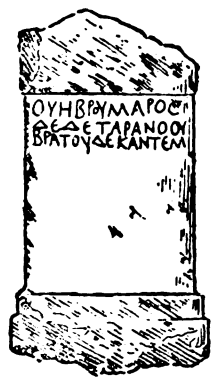

Verbumaros’ votive to Taranus

ουεβρουμαρος δεδε ταρανοου βρατου δεκαντεμ

uebrumaros dede taranou bratu decantem

“Uebrumaros gave unto Taranus due tithe.”

Without going into too much detail, the dedicant’s name may mean ‘rich in amber’ (amber jewelry being worn by chiefs in Welsh poetry), per Delamarre. However the Welsh cognate gwefr is found in river names and typically alludes to color, and color-based names typically referred to the person’s hair color. So, Vebrumaros might have been amber-haired.

The Gaulish God to Whom Vebrumaros offered is typically called “Taranis” today, following the spelling in Lucanus’ Pharsalia. But Gaulish votive inscriptions like the above imply a nominative of Taranus instead.

It’s anybody’s guess why Lucanus spelled it as Taranis. He wasn’t necessarily wrong! But I would argue the form found in Gaulish votives should be given more attention and precedence.

[C]artaros’ votive to the Namausican Matres

[-]αρταρ[ος ι]λλανουιακος δεδε ματρεβο ναμαυσικαβο βρατου δε[καντεν]

[-]artaros illanuiacos dede matrebo namausicabo bratu decanten

“**[C]artaros, (son?) of Illanuios, gave unto the Nîmoises Mothers due tithe.”

![[C]artaros’ votive to the Namausican Matres A grainy black and white photo of a low, flat capital that bears the votive to the Namausican Mothers, above a line drawing to show the inscription more clearly. The lettering is refined Greek capitals, and the capital itself is very wide and short, so it has enough room to fit the entire inscription on only two lines. The capital is plain, with no decoration.](https://skribbatous.org/user/pages/02.sanestos/rata/gallo-greek/matrebo_namausicabo.png)

Cassitalos’ votive to Ala[-]inos

κασσιταλος ουερσικνος δεδε βρατου δεκαντεν αλα[-]εινουι

cassitalos uersicnos dede bratu decanten ala[-]inui

“Cassitalos, Versios’ son, gave due tithe unto Ala[-]inos”

![Cassitalos’ votive to Ala[-]inos A text transcription of the votive. There is a line down the middle (after 5-6 characters per line) that separates the inscription in two, to represent the fact that the inscription was made across two contiguous faces of stone. Note that the sigmas are 'square,' similar to the shape of a left bracket: [.](https://skribbatous.org/user/pages/02.sanestos/rata/gallo-greek/alainui.png)

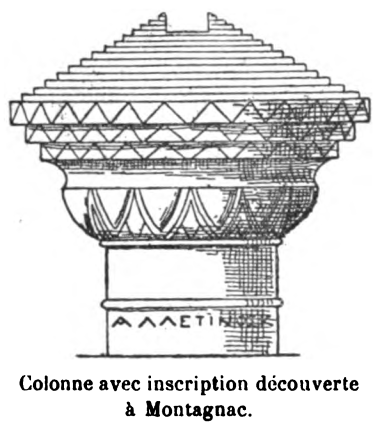

Alletinos’ votive to Carnonos Alisonteas

αλλετ[ει]νος καρνονου αλ[ι]σο[ντ]εας

allet[ei]nos carnonu al[i]so[nt]eas

“Alletinos to Carnonos of Alisontea”

There is some debate over how to read this inscription, and whether it is a votive or a funerary monument.

If not a funerary epitaph, then this is an abbreviated devotion (no verb or object offered) made to what is now one of the most popular gods in modern Paganism (depending on how one looks at things). In spite of its brevity, it is informative.

The word order suggests “Alisonteas” describes Carnonos rather than the dedicant. This could distinguish Him from the more well-known Cernunnos, whose inscription comes from Lutetia.

Besides the localized epithet, His name is spelled differently. It better matches the Proto-Celtic etymology proposed: *karno- ‘horn’.

This localized form of Karnonos is just one example of the polyvalence of this theonym.

An elusive inscription to the Cernunnae (feminine plural) has also been documented. This is frequently overlooked, as antlered, cross-legged female figurines get dismissed by authors as having no connection to the male Cernunnos.

A male, 3-headed statue from Condat, complete with a torc and holes where antlers could be mounted, may further exemplify the polyvalence of Carnonos in both gender and number, besides locality. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, how diverse religious expressions are to Him today...

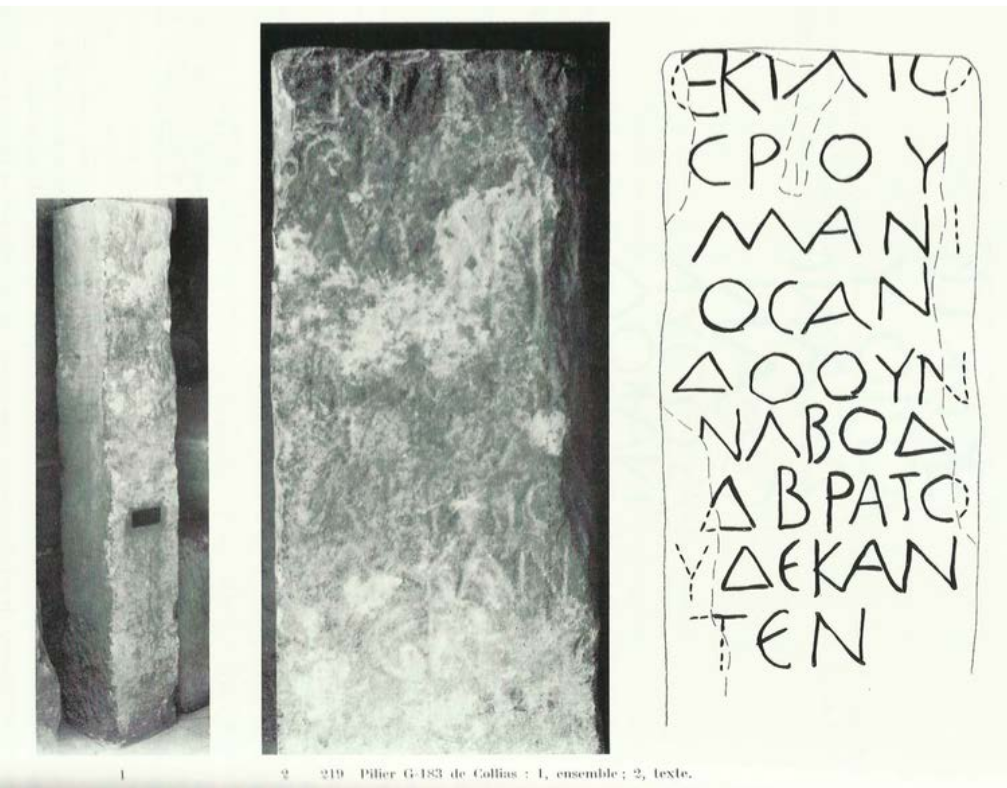

Ecilios’ votive to The Andounnas

εκιλιος ρ.ουμαν[ι]ος ανδοουναβο δ[ε]δ[ε] βρατου δεκαντεν

ecilios roumanios andounabo dede bratu decanten

“Ecilios of Romanos, unto The Andounnas, gave due tithe.”

The Andounnas are another example of plural Gaulish goddesses. Their name is generally agreed to mean something like ‘water below,’ in contrast with another attested theonym, Uxouna (‘water above’). These water-based epithets could be similar to the Nymphae, or they may derive from placenames.

If that’s the case, the epithet would fit in the genre of Gallo-Greek votives made to The Matres, like The Matres of Glanon and Namausos, for example.

But De Bernardo Stempel considers ithis a chthonic epithet:

“Given the Welsh comparandum annwn ‘underworld,’ older annwfn from *an(de)-dúbno-, a pluralized feminine derivative *An(de)dúbn-ai with haplology still emerges as the most adequate reconstruction for this theonym, which may have meant ‘The underworld [mother goddesses].’”

Votive terms and formulae

DEDE BRATVDECANTEM

Bratudecantem or -decanten (sometimes shortened as “bratu”) was the gift offered in all but two of the inscriptions.

One of the inscriptions was so concise it didn’t mention what was offered (if it is a votive at all).

Segomaros famously dedicated a nemēton.

A clear votive formula emerges:

When bratu is given, the verb dede is almost always used. This verb relates to that found in the touchstone Latin phrase “dō ut des” as well as Irish dán, and Welsh dawn.

EIVRV

Segomaros’ offering of a nemēton was given by a different verb: eiuru. This is perhaps related to the word I understand to mean ‘dedicants’: eurises. Although it only appears once in Gallo-Greek votives, we see more of it in the Italic inscriptions.

Anððerí (uncertain ones)

-

Altar to the spring God Graselos — From a nymphaeum in Vaucluse, this beautiful altar was repurposed in the Christian era as a pedestal for a chapel’s iron cross, which no doubt ironically led to its preservation.

The Γ and Ρ are missing from the damaged inscription, but Graselos’ name is partially reconstructed based on a toponym that was documented in that area as “Grasello.” Thus, Graselos is believed to be the local spring God.

-

Votive from Nemausos — Two limestone blocks, which may have supported a statue to a Goddess were dedicated by Nertomaros and N[.....]maros, sons of Boios. The verb in this case is ειωραι, which Stifter says may be in the dual, and compares it to ieuri from the Gallo-Latin “rigani rosmertiac” inscription.

The middle block is missing, so unfortunately we do not know the theonym, among other elements that are missing from the inscription.

-

Capital to a God — A capital in the same style as the beautiful votive to the Matres Namausicas.

Bratudek[antem] was given by a son of Adressios, to a God Whose name ends in -os.

-

Altar from the baths of Glanum — This altar is not complete, so we don’t know which God it was dedicated to. The dedicant’s name may be read as Καμουλατια (Camulatia), which is strengthened by also being attested in a Gallo-Latin inscription from Nîmes (CIL XII 3645).

Camulatia might be a theophoric name in honor of Camulos. The ending -latia might also be found in the name from the next inscription. Lati- could relate to *lāto- ‘fury,’ meaning something like a warrior, or to *wlati-, meaning a ‘ruler’ or prince. (‘Princess’ in this case?)

-

Stone shard — One reading says this was dedicated to an unheard-of God named Konnos, by a woman whose name ends in -latia. This would seem plausible, except for Konnos being an unusual theonym.

An alternative reading is that a man named Konnu (a known personal name) dedicated this to the Matres [Ου]λατιαϐο *Wlatiābo (Sovereign Matres), who are also attested elsewhere in Narbonensis. This is more satisfactory overall, but has an unprecedented word order.

Both interpretations are challenged by the fragmentary state of the inscription.

-

Footprint stela from Vaucluse — Uncertain, but possibly a votive to a Goddess named Aiuniā (dat. αιουνιαι). This corresponds to a personal name, Aiunus, known from Iberia, whose root may be aiu- ‘eternity.’

This also resembles the form of a reconstructed theonym from De Bernardo Stempel: *caimíniai (> MATRONAE CAIMINEAE).

- Inscription from Vaucluse (of debatable Celticity) — Possibly reads, “To Velros, from Becicnos”?

- Votive fragment — This beautiful votive fragment possibly reads *βρατουτον. It may be a participle (‘offered’) or noun (‘offering.’)

- Stela to Belenos?

- Basin to Belenos?

- Wall inscription to the Matronas?

- Lost altar to Dios?

- Lost votive from Nîmes to fountain Goddess?

- Lost bilingual capital from Nîmes

There are a few more probable votive inscriptions, but which are merely ceramic or lead fragments that only preserve part of the dedicant’s name (so no verb or theonym, and no clear religious medium such as an altar).

Another votive basin may have been found recently, but the findings are not yet published as of this writing.