Caduceus

One of Mercury’s or Hermes’ most iconic possessions is His wand or “herald’s staff,” a symbol which remains ubiquitous today but whose design and meaning has changed in major ways since ancient times. This article aims to breakdown its original attributes, history, and symbolism that are largely forgotten today.

Table of Contents

History and uses

Properly known as a κηρύκειον (kerykeion, from Greek κῆρυξ ‘herald’), which was adapted as caduceus in Latin, the staff was not unique to Hermes. It existed as an actual physical object carried by heralds to prove their authenticity and authority to deliver messages for those in power 2 — and by extension to assure their protection while traveling sometimes hostile territory to do so.

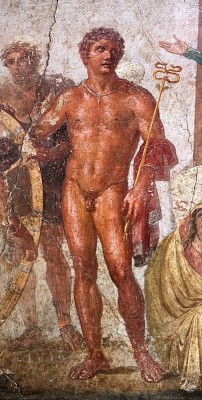

The caduceus was also a priestly instrument. Multiple Roman frescoes (see below) show priests of Isis wielding it as the Goddess greets Io. Men known as caduceators also wielded it as part of their role in brokering peace negotiations, according to Servius, who compared them to the fetial priests responsible for war (see section “Caduceus as a Peace Sign”).

Besides priests, a number of Goddesses also carry the caduceus, such as Iris (a winged angel of Hera and the Olympians), Felicitas, and Pax. Nike or Victoria have also sometimes been said to carry it, though I cannot find an example that positively identifies Them over Iris or Pax. Additional figures in art who carry kerykeia include mortal heralds such as Talthybios (from the Trojan War).

Fig. 3. Bronze caduceus from Centum Prata (Switzerland), 1st – 2nd cent. CE.

Hermes’ association with the kerykeion is nearly absolute in visual art even from the earliest times, but the literary or mythological sources painted a murkier picture. Hermes was not initially said to have a herald’s staff, per se, and His staff, or wand, was ascribed a number of other properties.

The Iliad 1 and Odyssey 3 tell us Hermes has a golden wand (ῥάβδος, rhabdos) with the power to both lull and raise mortals from sleep, and with which He leads shades to the Underworld.

Fig. 5. The mortal herald Talthybios from the Trojan War, with kerykeion.

The Homeric Hymns4 recount that Apollo gave Hermes a golden wand (ῥάβδος, χρυσόρραπις, rhábdos, chrysórrhapis) in exchange for Hermes’ vow to not steal from Him again. This wand is said to have three branches (τριπέτηλος, tripételos), to keep its bearer unscathed, and to help accomplish any task that is Good. Apollodorus5 alternatively relates that Hermes traded His panpipes for the wand, and that Apollo had used this wand for herding cattle.

It’s not until around seven centuries later that we find literary myths more clearly describing the caduceus depicted in art, and explaining its invention6 — i.e., that Mercury used a “small rod” (virgula, rhabdos) to intervene in a fight between two snakes which then intertwined in union around it.

Caduceus design

[The caduceus] shows a pair of serpents, male and female, intertwined; the middle parts of the serpents’ coils are joined together as in a knot, called the knot of Hercules; their upper parts are bent into a circle and complete the circle as they meet in a kiss; below the knot their tails rejoin the staff at the point at which it is held, and at that point appear the wings with which they are provided.

— Macrobius 7

Macrobius provides us with a succinct explanation of the canonical caduceus’ design that could hardly be improved upon, to which I would only note some stylistic variations in how it was rendered in works of art:

Fig. 9 Gallo-Roman silver statuette of Mercury with a “wire-wrap” caduceus.

- Wings — Wings weren’t originally part of the kerykeion, but in Roman art become typical of the caduceus (perhaps to distinguish between the staff of Mercury and other Gods vs. mortal heralds’ staves). The wings can vary in size and shape, sometimes being like hummingbird or sparrow wings, while other times having a large span like swan wings.

- Level of detail — The kerykeion is often shown abstract so that even key details like the snakes or knot cannot really be discerned. This probably owes to the difficulty of rendering such details, especially in small formats like vase paintings. We find actual bronze kerykeia do feature serpents from at least the 5th cent. BCE (cf. fig. 26 & 29), so they are seemingly an original component even if vase paintings do not reflect that. Later Roman frescoes, by contrast, seem more committed to rendering those details.

- Enclosure — How close the snakes come to meeting in a kiss can vary considerably. Especially in early vase paintings, the top of the kerykeion is shaped like a ring and crescent (like the symbol Taurus), while later on the snakes actually achieve a figure-8, or at least come close to it.

- Radius — The curvature of the snakes’ bends were originally circular, but in Roman art they can also be very oblong to the point of being oval or pill-shaped.

- Thickness — Frescoes can show rather thin, twisty, even wispy looking caducei, while vase paintings show somewhat more solid looking ones, and sculpted or cast kerykeia were even sturdier than that. However, some small-format metallic figurines have survived with caducei that were made using a wire-wrap technique. This suggests to me that even the most thin and bendy looking caducei in art are not a painter’s invention, but probably represented actual metal working styles that were in use to craft them.

Ancient vs. modern

The caduceus is ubiquitous even in modern times, albeit with a transformed design that has minimal resemblance to the caducei of antiquity. Probably the only modern context where we find the original caduceus preserved would be in a very abstract form for the astrological and alchemical signs of Mercury:

Fig. 14 Unicode symbol for Mercury, c. 1993 CE.

Instead, the modern caduceus has basically been inverted, with enlarged wings perched on top and the two snakes coiling loosely around the rod below in a double-helix, usually tapering as they go down:

Fig. 16 Clipart of a modern caduceus.

While I’ve yet to find an explanation for why this transformation took place, it provides a useful diagnostic for identifying whether an artifact is actually ancient or not (sometimes Renaissance and Modern bronzes of Mercury get mistaken as Roman). Occasionally, genuinely ancient statues are displayed in museums with the modern caduceus, but those are the result of latter-day (usually Renaissance to 17th century) “restorations.”

The modern design of the caduceus stems from Renaissance art, where the double helix snakes were firmly established from the beginning, albeit often without wings. There seem to be few depictions of Mercury in the preceding Medieval era, but the few that I’ve found seem to supply Him with a plain rod, or mace. Both instances could reflect artists producing designs based solely on Classical literary sources available to them, almost all of which did not elaborate on the visual details of the conventional caduceus.

However, there are one or two artifacts from Late Antiquity that might point to a much older visual history for the “double-helix” design:

The first is a Corinthian capital from Auxerre, France. It once had three Gods and a Goddess on its four faces, but now only Mercury remains. It bears the overall appearance of an ancient Roman capital, albeit with a couple details that call its periodization into question. The first is obviously the double-helix caduceus, for which we have no other examples of in Roman Gaul. The second is the hairstyle: Roman Gaulish sculptures of Mercury with enough size and detail always show Him with very curly hair, usually rendered with spherical curls. The combed-straight hair on this piece makes it incredibly suspicious, to me.

Mercury’s overall style here looks reminiscent of one of Raphael’s depictions (e.g., from his “Loggia of Psyche”). And there are possibilities for why even a Renaissance artifact could wind up so fragmented (Huguenots destroyed Catholic buildings when they took over the city in 1567). But there is one other artifact of provable antiquity that leaves open the possibility that a sculpture with this style caduceus could be authentic:

A remarkable 4th century CE Spanish mosaic at Casariche shows the “double helix” type caduceus clear as day. The Casariche design is provably authentic, as it was discovered in 1986 and documented in situ by archaeologists. There are no signs that the Casariche site remained in use past the Roman period, so later alterations or repairs could not explain its design, either.

Interestingly, both works probably post-date the Christianization of their locales (the Casariche mosaic is 4th century, and Auxerre was evangelized rather early with bishops being sent there since 258 CE). So it would be interesting to consider whether Christianity had any influence on the redesign of the caduceus for one reason or another, although we may never discover how or why the change occurred.

Fig. 19 Illustration from 15th cent. Italian manuscript.

The caduceus doesn’t reemerge in the surviving art record, as far as I could find, until over a thousand years after the Casariche mosaic, when we finally see it again in a 15th century manuscript (fig. 36), predictably with a double-helix design. The caduceus’ use in art grows very common thereafter.

Caduceus as a Peace Sign

Whose hand contains of blameless peace the rod, Corucian, blessed, profitable God;

— Orphic Hymn to Hermes 9

[Mercury] threw his staff down between the two [snakes] and, lo, they left off fighting; and so he said of the staff that it was appointed to make peace.

— Hyginus 8

Fig. 20 was probably promoting Caesar’s rhetoric of reconciliation during the Civil War.

While largely forgotten nowadays, the caduceus was widely understood in its time as a symbol for Peace. Authors often credit the caduceus’ power to end vitriol and fighting to its visual symbols, the circumstances of its creation, and of course the power of Mercury or Hermes. This is no doubt true, but there are no less interesting mundane reasons for why caducei probably became associated with Peace, as well.

Naturally, heralds were responsible for delivering the news of ceasefires and peace accords. As Servius explains, even the men in peace envoys who negotiated such agreements carried the caduceus. It makes sense that anyone who needed to prove their authority at the negotiating table would either carry the instrument, or be accompanied by someone who does. And as they would possibly have to travel through hostile territory to get there, the caduceus could help assure their protection. Much like noncombatants today who mark themselves with the Red Cross, or blue flak jackets emblazoned with “Press,” the caduceus would have played a part in protecting the bearer from attack — i.e., “don’t shoot the messenger.”

All of this naturally converges to make the caduceus a symbol of Peace, one that was minted on coins to advertise policies of reconciliation, or tout the Pax Romana where it is literally wielded by Pax Herself.

The serpents coiled round the [caduceus] … are a symbol of the fact that even savage men are charmed and bewitched by [Hermes], who loosens the conflicts between them and binds them with a knot which is difficult to untie. For this reason the caduceus appears to be a symbol of peace-making.

— Cornutus 10

This is the explanation of this wand: Mercury is called both god of speech and the spokesman of the gods; thus the rod separates the serpents i.e. poisons. For instance, warring peoples are pacified by the words of spokesmen. That is why, according to Livy, peace negotiators are called caduceators. That is to say, just as wars used to be declared by fetial priests, so peace was made by caduceators.

— Servius 11

Figures

- “Punishment of Ixion,” 4th style (60-79 CE) Pompeiian fresco from House of the Vettii. (Source). ↑

- Bronze kerykeion, from Longane (Sicily), c. 450-420 BCE. (Source). ↑

- Bronze caduceus from Centum Prata (Switzerland), c. 1st to 4th cent. CE. Stadtmuseum, Rapperswil. (Source). ↑

- Attic red figure attributed to the Berlin painter, c. 480-470 BCE. See entry at Musée du Louvre for more detail. (Image source). ↑

- Attic Red-figure skyphos attributed to the Macron painter, c. 480 BCE. See entry at Musée du Louvre for more detail. (Image source). ↑

- Fourth Style fresco from the Temple of Isis, Pompeii, c. 1st cent. CE. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples (source). ↑

- Small bronze caduceus, 1st cent. CE. See entry at Museum for Kunst and Gewerbe Hamburg for image source and details. ↑

- Collection of southern Italian and Sicilian kerykeia, 5th to 4th cent. BCE. See individual entries at Museum for Kunst and Gewerbe Hamburg for more detail. (Image source). ↑

- Silver and gold-leaf statuette (56 cm) from the Berthouville Treasure, 1st to 2nd cent. CE. See entry at Bibliothèque nationale de France for more detail. (Image source). ↑

- Bronze Bactrian coin of Demetrius I (c. 200-180 BCE). (Image source). ↑

- Roman bronze statuette of Mercury from Obernburg am Main, c. 2nd cent. CE. Archäologischen Staatssammlung in München. See German-language article for more info and photos. (Image source). ↑

- Roman bronze statuette of Mercury, found at the necropolis in Reinheim, c. 3rd cent. CE. Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte des Saarlandes. See German-language entry at Museen in Saarland for more detail and photos. (Image source). ↑

- Bronze coin from Sardis (Turkey), c. 140-144 CE. See entry at Digital Coin Cabinet of the Institute of Classical Archaeology of the University of Tübingen for more details. (Image source). ↑

- Unicode character for the astronomical and astrological symbol of Mercury. (Image source). ↑

- Detail of a fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, from the Palazzo Clerici, Milan, c. 1740 CE. (Image source). ↑

- Clipart of a modern caduceus. (Source). ↑

- Limestone capital of Mercury, Apollo, Mars, and unknown Goddess, date unknown. Discovered near the lock of the Bâtardeau in Auxerre, 1789. See entry at the Corpus RBR for more detail. (Image source). ↑

- Juicio de Paris mosaic from the Villa del Alcaparral in Casariche (Spain), c. 4th cent. CE. (Source). ↑

- See articles at Ayuntamiento de Casariche and Crónicas de Casariche sites for more details.

- Illustration of Hermes by Ciriaco d'Ancona, Italy, c. 1474 CE. Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Canon. Misc. 280. ↑

- Roman denarius, c. 48 CE. (Image source). ↑

- Rome mint coin, c. 138 CE. (Image source). ↑

- Ephesus mint tetradrachm, c. 28 BCE. (Image source). ↑

- Aureus, c. 41-42 CE. (Image source). ↑

References

- Iliad book 24. Homer. 8th century BCE.

- The Iliad of Homer, book 24 p. 453, T.A. Buckley (Trans.), 1860. ↑

- Thucydides 1.53.

- The English works of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury. Thomas Hobbes (Trans.) 1843. ↑

- See also note 53.18 (E. C. Marchant, trans.)

- Odyssey book 24. Homer. 8th century BCE.

- The Odyssey, book XXIV, p. 310. S. Butler (Trans.) 1900. ↑

- Hymn 4 to Hermes. Homer. 6th century BCE.

- The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation. H.G. Evelyn-White (Trans.) 1914. ↑

- Bibliotheca 3.10.2. Apollodorus. 1st or 2nd cent. CE.

- Apollodorus, The Library. Sir James George Frazer (Trans.) 1921. ↑

- Siebert Gérard. « L’invention du caducée. » In: Ktèma : civilisations de l'Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques, N°21, 1996. Hommage à Edmond Frézouls – III. pp. 344-345. ↑

- Saturnalia 1.19.16. Macrobius, c. 431 CE.

- The Saturnalia. Percival Vaughan Davies (Trans.), Columbia University Press, 1969. ↑

- De Astronomia, Gaius Julius Hyginus, 27 BCE – 14 CE.

- For original Latin excerpt, cf. ref. 6.

- The Poeticon Astronomicon. Mark Livingston and D. Neel Smith (Trans.), Allen Press 1985. ↑

- Orphic Hymn to Hermes. 2nd — 3rd cent. CE.

- The Mystical Hymns of Orpheus. Thomas Taylor (Trans.) 1824. ↑

- Ἐπιδρομὴ τῶν κατὰ τὴν ἑλληνικὴν θεωρίαν παραδεδομένων (Epidromē tōn kata tēn hellēnikēn theōrian paradedomenōn, better known as, Theologiae Graecae Compendium, or “Compendium of Greek Theology”). Lucius Annaeus Cornutus, c. 1st cent. CE.

- Cornuti Theologiae Graecae Compendium, p. 22. Cornutus, Lucius Annaeus, and Carl Lang. Teubner, 1881.

- An etymological commentary on Cornutus' Epidrome, p. 126. Anscombe, Jeremy Guy. PhD thesis, University of Leeds. 2005. ↑

- Commentaries on the Aeneid, 4.242, Servius, turn of the 4th to 5th cent. CE.

- Latin text available at Perseus Tufts: Maurus Servius Honoratus. In Vergilii carmina comentarii. Servii Grammatici qui feruntur in Vergilii carmina commentarii; recensuerunt Georgius Thilo et Hermannus Hagen. Georgius Thilo. Leipzig. B. G. Teubner. 1881.

- English translation from McDonough, C. M., Prior, R. E., Stansbury, M. (2004). Servius' commentary on Book four of Virgil's Aeneid : an annotated translation, p. 57. ↑